More than 20 years have passed since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, yet questions continue to linger—not just among fringe theorists, but among thoughtful professionals who witnessed discrepancies that still haven’t been addressed.

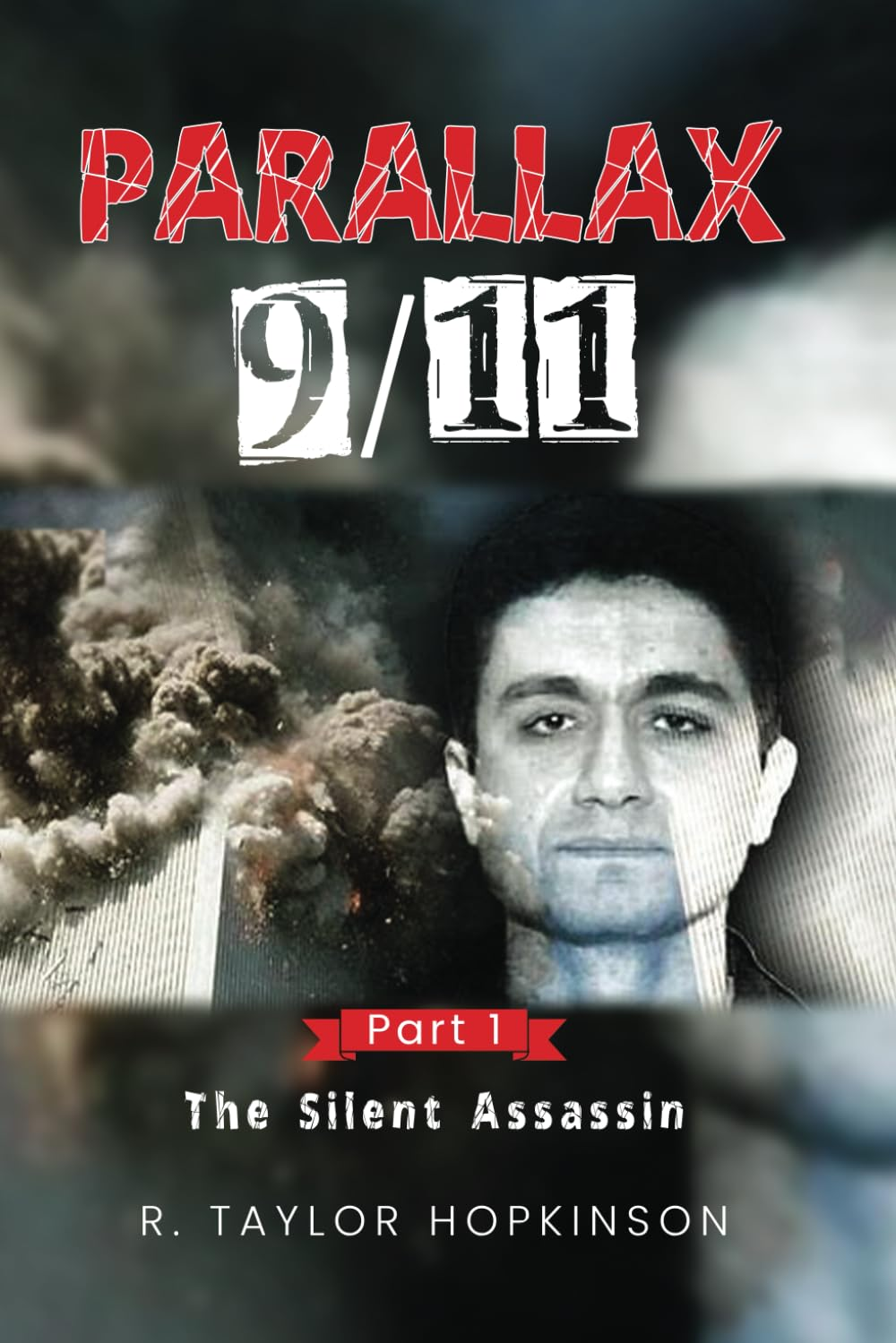

In Parallax 9/11: Part 1, author and retired lawyer R. Taylor Hopkinson takes readers on a journey that quietly, but powerfully, suggests we may not know the full story. Through his investigation into the death of a British man in Florida—Keith Chapman—Hopkinson uncovers what appears to be a direct and early encounter with 9/11 ringleader Mohamed Atta, well before the official timeline claims he arrived in the United States.

If Atta was in Florida in April or May 2000, as multiple witnesses claim, and if he made violent threats and discussed intentions tied to Bin Laden and U.S. landmarks, why wasn’t this information central to the 9/11 Commission Report?

Johnelle Bryant, a USDA loan officer, gave a detailed public account of her meeting with Atta, during which he requested $650,000 to modify a small aircraft, discussed “crop dusting” applications, and explicitly mentioned Bin Laden and the Pentagon. She even passed a lie detector test. Yet her story was relegated to the margins.

Hopkinson’s own legal case, representing the Chapman family after Keith’s fatal hit-and-run in May 2000, uncovered even more. Friends of the deceased later recognized the man driving the car as Mohamed Atta. They had no prior suspicions until his photo appeared on the news after 9/11. Their reaction was instant: that was the man. The car, the face, the presence—etched into memory.

The author is careful not to claim a conspiracy, but he does raise essential questions about the completeness of the official narrative. He presents real people, sworn testimony, and unexplored threads—stories that, together, call for a deeper review.

So, is it time to reopen the 9/11 investigation?

Not necessarily to challenge the central facts—that planes were hijacked, that lives were lost, and that al-Qaeda was responsible. But to fill in the silences, address inconsistencies, and, most of all, ensure that every victim, including those forgotten by history, receives the full truth.

A reopened investigation wouldn’t have to be adversarial. It could be restorative. It could include civil perspectives, legal cases, and international voices that have gone unheard. It could finally examine cases like Bryant’s, like Chapman’s, and like those of countless others who intersected with the perpetrators before the towers fell.

We don’t question the moon landing every year, but we do revisit it with new data, new declassifications, and new understandings. Why should 9/11 be exempt from such continued reflection?

Hopkinson’s book doesn’t accuse—it illuminates. And in doing so, it makes a quiet, crucial case: that if there are holes in our collective memory, we owe it to the victims, the survivors, and future generations to patch them with truth.

Parallax 9/11: Part 1 is a call for accountability, compassion, and curiosity. It asks what justice looks like when history moves too fast to catch every detail. And it offers something rare in the 9/11 conversation—a new thread worth following.