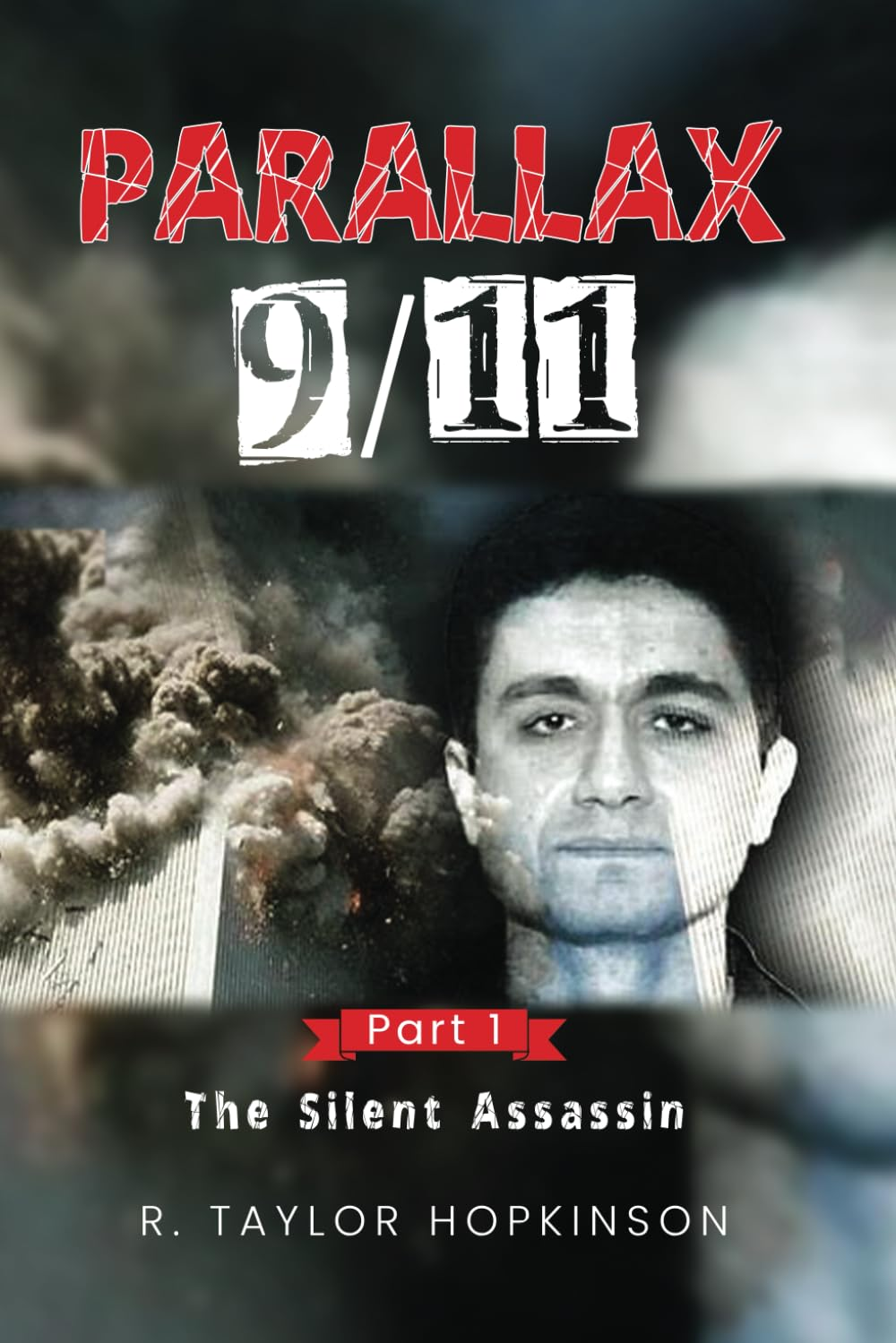

R. Taylor Hopkinson wasn’t a politician, intelligence agent, or investigative journalist. He was a practicing injury claims lawyer in the UK when the events of 9/11 unfolded. But he had a front-row seat to a case that may have intersected with the man at the center of it all—Mohamed Atta.

In Parallax 9/11: Part 1, Hopkinson blends his legal expertise with lived experience, offering a rare lens on how early warning signs can go unnoticed, even when they’re in plain view.

The story began with what seemed like a tragic accident. Keith Chapman, a lively and much-loved British man, was killed in a hit-and-run incident while on a golfing holiday in Florida in May 2000. Hopkinson represented Chapman’s grieving family in their pursuit of compensation and answers. But the case took an unexpected turn more than a year later, after the world saw Atta’s face on every television screen following the 9/11 attacks.

Two key witnesses—Keith’s close friends who had seen the crash—recognized Atta immediately. Their certainty wasn’t vague or speculative. It was instant, emotional, and confirmed in follow-up interviews.

From a lawyer’s perspective, that kind of recognition isn’t taken lightly. Eyewitness testimony is carefully scrutinized, and Hopkinson applied the same rigorous standards to their statements as he would in any injury or fatality case. He found no motive for deceit, no inconsistencies, and no benefit to their claims—only a need to be heard.

He then learned of another strange incident. Around the same time as Chapman’s death, Mohamed Atta had allegedly applied for a $650,000 agricultural loan from the USDA. His purpose? To convert a small plane into a crop duster. During the loan interview, he referenced Bin Laden and made veiled threats of violence. These were not the words of a man with a farm in mind.

As Hopkinson put the pieces together, a broader pattern emerged—of bureaucratic gaps, missed red flags, and a tragic underestimation of what individuals like Atta were planning.

From a legal standpoint, the failure wasn’t just governmental—it was systemic. Had Atta’s behavior during the loan interview been flagged and followed up, had the Chapman incident received deeper investigative attention, perhaps dots could have been connected earlier.

Hopkinson isn’t arguing that 9/11 could have been prevented by his case alone. But as a lawyer, he knows that justice is built on detail. And when key details are dismissed or forgotten, entire systems fail.

Parallax 9/11 is his way of making the case—not in court, but in public. He presents facts, timelines, and testimony. He shows readers how a legal professional processes a chain of events. And he reminds us that sometimes, the people closest to the ground—not in Washington, but in small offices and local courtrooms—see the cracks before anyone else.

This isn’t a lawyer exploiting a tragedy. It’s a lawyer using his skill set to honor it, investigate it, and bring clarity where confusion has reigned.

For anyone curious about the overlooked legal signals of 9/11, Parallax 9/11: Part 1 is not just a book. It’s evidence. It’s insight. And it’s a case still open to interpretation.