In the weeks following the September 11 attacks, the world struggled to comprehend the scale and complexity of the operation that had just unfolded. How had 19 men orchestrated such devastation with such precision? What red flags had been missed? And what early clues were buried in bureaucratic paperwork, unnoticed and unconnected?

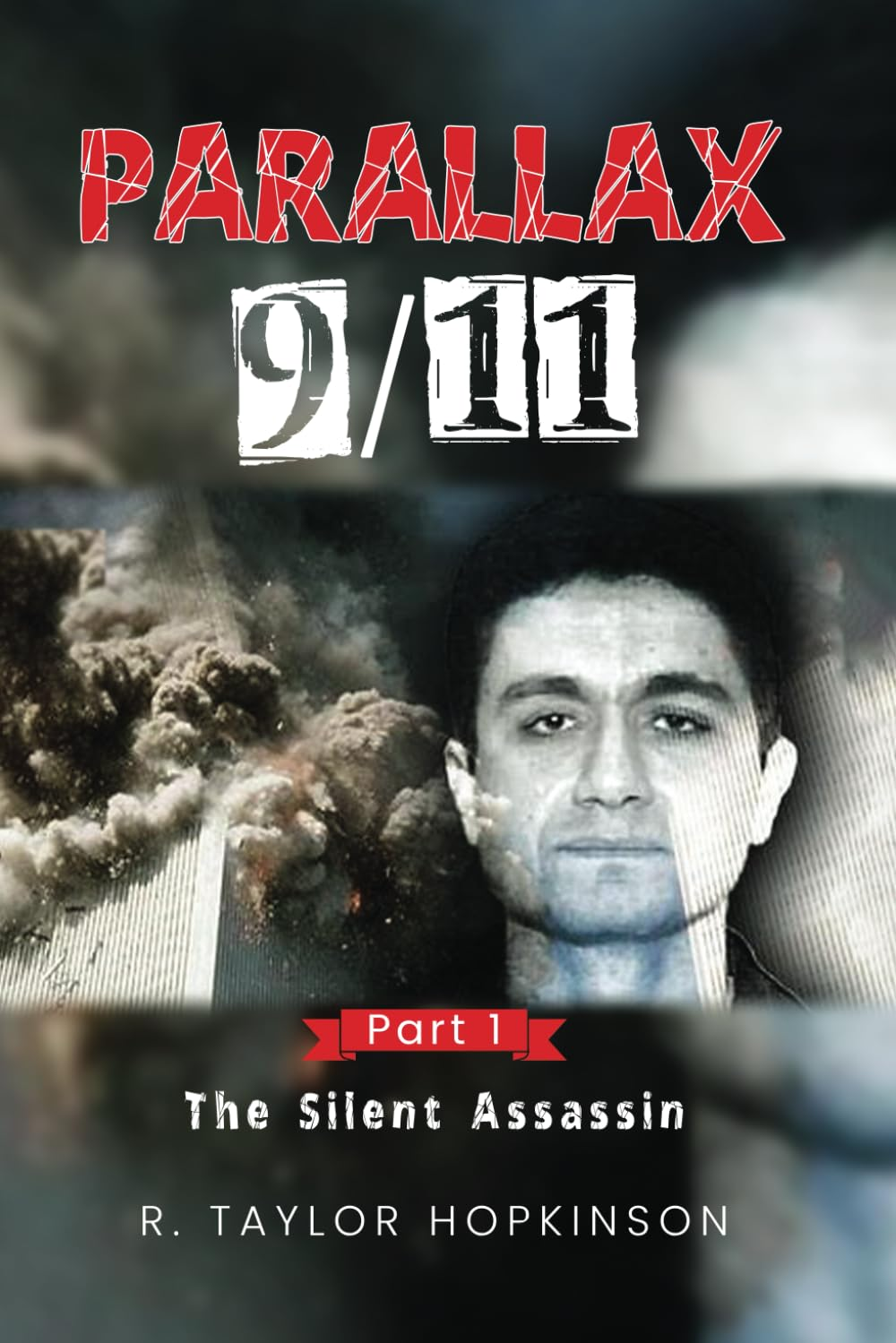

Parallax 9/11: Part 1 by R. Taylor Hopkinson explores one such overlooked clue: a strange, unsettling loan application submitted to the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the spring of 2000—over a year before the Twin Towers fell. The applicant? A man who later became the face of terror—Mohamed Atta.

The encounter took place in Homestead, Florida. Johnelle Bryant, a loan officer with the USDA, reported that a man identifying himself as Atta came to her office requesting $650,000 to buy and retrofit a small aircraft. His intended use was crop dusting. But he wasn’t a farmer. He had no business history in agriculture. What he did have was a deeply unnerving presence and an obsession with planes, chemicals, and American landmarks.

According to Bryant’s account, Atta mentioned Bin Laden by name, talked about the Pentagon, and appeared increasingly agitated when it became clear the loan wouldn’t be approved. He suggested that he could simply take the money by force and even commented on Bryant being alone in the office with no visible security. It wasn’t just an odd encounter. It was a threat—one delivered with cold precision.

Bryant would later pass a polygraph test confirming her version of events. But despite the credibility of her testimony, her story was not a focal point of the 9/11 Commission Report. Nor did it appear to trigger any kind of early warning investigation. Instead, it was quietly noted, categorized, and left to gather dust—just like the application Atta never formally completed.

In Parallax 9/11, Hopkinson doesn’t just recount this event. He contextualizes it, connecting it to the broader timeline of Atta’s movements and to a fatal accident case he was handling at the same time. Hopkinson’s client, Keith Chapman, died in May 2000 in a hit-and-run in Florida. Friends present at the scene would later identify the driver as Mohamed Atta. This too occurred before the official timeline places Atta in the country.

If these accounts had been taken seriously—if the crop duster application had triggered a cross-agency alert, or if the inconsistencies in Atta’s travel records had been flagged—might the trajectory of history have shifted?

The question is haunting, not because it suggests a clear moment of prevention, but because it reveals how terror doesn’t always hide. Sometimes it walks right into a government office, fills out a form, and talks about its plans in plain English. The problem is not only what was said, but that no one followed up.

Hopkinson’s book isn’t speculative fiction. It is grounded in real conversations, legal documentation, and a methodical investigation that calls into question the idea that there were no early signs. The crop duster application was one of those signs—clear, documented, and verifiable. And yet, it remained an isolated story, disconnected from the central narrative.

What Parallax 9/11 asks readers to consider is not whether history can be changed, but whether our systems are built to recognize danger when it comes in unusual forms. A fake business plan. A polite conversation laced with threats. A casual reference to a global terror leader. These are not the moments history books often capture—but they matter.

The crop duster application may have seemed like a footnote in the vast tragedy of 9/11. But in Hopkinson’s telling, it becomes a turning point. A moment when someone looked evil in the eye, asked questions, and still didn’t get the alarm bell heard.

Parallax 9/11: Part 1 is not just a retelling of the past. It is a call to learn from it—and to never again overlook the warning signs that hide in plain sight.